By Conner Tighe

As summer evolves into full bloom, our noisy friends are returning from a long retirement underground, the cicada. Every year, warm weather and mosquito swats will be joined by the cicada’s aggressive humming, making their nests in trees and plants. What most people might not know is that this year falls on the 17th year of the retirement, where three specific groups of cicadas will return to above ground level only to return underground after this season for another 17 years.

Crickets produce a similar phenomenon to cicadas by rubbing their wings together to create the familiar sound some might find comforting or annoying, depending on who you ask. Cicadas, like crickets, produce noise with their body but with a small organ called the tymbal. On it lies a series of ribs that, when buckled together, create the familiar cicada hum. Contrary to what you might hear, these insects are harmless to humans, and the most trouble you’ll get from them is the noise.

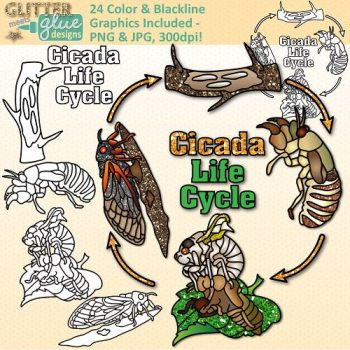

The annual cicadas heard every year around this time are called just that, annual cicadas. The others referred to previously are slightly different, coming out only every 13 or 17 years to make some racket. Both annual and periodical cicadas emerge from their hard shell after nesting on a vertical stand of some sort after emerging from the ground. The 17-year cicadas come from the northern United States, and the 13-year cicadas come from the southern portion of the U.S.

Although scientists know several cicada species hibernate only to emerge over a decade later, the reason for the unusual behavior is unknown. Many theories have gone into the reasoning behind this, like climate change which has caused fluctuations in temperature. Even with their three to four-year lifespan, cicadas outnumber predators, which has led to a continuous reproduction rate and has ensured their evolution and survival.

The cicada shares similarities with the locust, another sizeable flying insect. However, the differences outweigh its similarities. Although they have large wings, Cicadas are incapable of flying more than a few hundred feet or more. They also don’t destroy crops like locusts, but they will lay their eggs on plant stalks and leaves after the mating season. The cicadas are expected to remain above ground for roughly five to six weeks before returning underground. The insects continue to leave their mark every year with the shells they leave behind and the anticipation for another noisy summer to come.

Sources: Nature Museum, Scientific American, Southwest Journal, CBS News

Featured Image: NC State University